Dork Camp- the Lesbian Lovable Loser in Popular Culture

After the 2019 Met Gala, which featured Camp as its theme, the internet was alight with debate on what counted as Camp (Vogue). Which celebrities, after turning up in their exuberant costumes had succeeded and which had failed hilariously. Camp as a subject is notoriously hard to define. Even its seminal work, Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on Camp,” is just that- notes. A series of bullet points explaining what Camp is and isn’t, but never giving it a real definition. The conclusion, as typically happens when one tries to define an aesthetic movement, seems to be that you know it when you see it.So, when Mikaella Clements put out her seminal work, “Notes on Dyke Camp,” a sort of addendum(?)/response(?) to Sontag’s essay, I was super on board. I cannot explain Dyke Camp either, but I see it, and I know it. I’m getting ahead of myself, however. For the uninformed, let’s start with regular old Camp. What is it? Sure, you can’t define it, and “to talk about [it] is therefore to betray it,” (Sontag) but come on. Broadly speaking, Camp is an aesthetic movement that takes joy in that which is so over-the-top it becomes fun. I like Wikipedia’s definition quite a bit, actually: “[Camp is] an aesthetic style and sensibility that regards something as appealing because of its bad taste and ironic value.”The concept of Camp has been around for decades, though perhaps the modern understanding of it is lacking. Camp as it is known today is somewhat bizarrely exclusive. It is largely associated with the upper classes, and with queer men- as well as the (often straight) women that queer men love. Elton John, Lady Gaga, Cher, Alan Cumming, and Prince all jump to mind when the word Camp is used. A uniting theme here seems to be femininity, exaggerated or made comical in some way- either by its performance or who’s doing the performing. Much of Camp comes about from male-presenting people leaning into feminine aesthetics. Fun as it certainly is, this can come with the unfortunate implication that only the feminine is funny, ridiculous, trivial, Campy.In “Notes on Dyke Camp,” Clements proposes the naming and acknowledgement of a subset of, or perhaps counterpart to, traditional Camp, which she calls Dyke Camp. Dyke Camp is nebulous, like traditional Camp, but it too is an aesthetic movement that can be found in people, clothes, performances, places, and objects. It has a similar belief system that the bad is good, and Too Much is great. This time, however, WLW (women who love women) have the reins, and we decide what constitutes those descriptors. Says Clements: “it’s a movement directed, for the first time, not by the tastes of gay men but gay women: a specific brand of humor, manners, and sensibilities guided by lesbian identity.”Dyke Camp shares common ground with traditional Camp, but it is certainly its own beast as well. While traditional Camp often references the mannerisms of feminine seductiveness, Dyke Camp leans into masculine swagger and cockiness. That, or the also-notorious struggle of men to meet these patriarchal standards, which I’ll elaborate on when I discuss the Lesbian Lovable Loser. In contrast with traditional Camp’s appropriation of the feminine, Dyke Camp often employs masculine aesthetics or the concept of masculinity as a performance. Clements herself would disagree with me saying that, actually. Early on in her Notes she makes it clear that Dyke Camp is “not so interested in the playfully rigid binaries of butch/femme” and that assuming it is inherently masculine is as wrong as assuming Camp is inherently feminine. Respectfully, I disagree, but only as far as her essay seems to object to as much as the acknowledgement of the prevalence of traditionally “male” aesthetics in Dyke Camp.Masculinity, or “masculinity,” in quotes, is far from the only thing that makes Dyke Camp itself, of course. However, I don’t see the harm in acknowledging that playing with its aesthetics is a regular occurrence. A drag queen dressed as Marilyn Monroe would take the essence of her femininity and make it the show, blowing up her hair, pushing her figure to extremes, and donning the brightest of red lipsticks. Conversely, the performers of the Lessons with K.O.K. TikTok videos have made masculinity- namely, the mainstream archetype of the "frat bro"- their playground. Backwards caps, brightly colored button-downs, the blatantly deepened voices and comic tone with which the information is delivered all come together to make an excellent Dyke Camp performance.

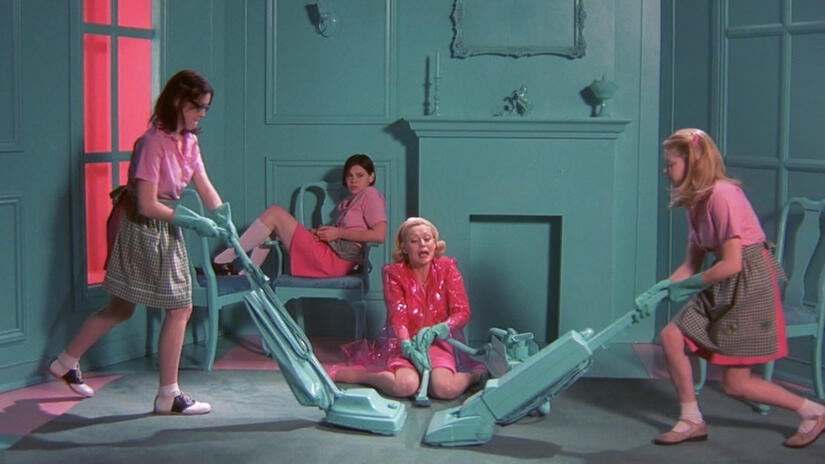

Note: from here on out, I will be referencing a lot of real people as examples of Dyke Camp, and I must clarify upfront that me putting their performances in this category is not an assumption of their identities. Like camping doesn’t make you a gay man, performing Dyke Camp doesn’t make you a lesbian, or any shade of queer woman. Anyone, of any gender or sexuality, can do Dyke Camp. With that out of the way, let’s carry on.The type of masculine signifiers Lessons With K.O.K. makes use of are so powerful that a full commitment to costume isn’t necessary. In a similar TikTok video, which never fails to make me laugh out loud, performers with highly feminine hair and makeup mug at the camera to emotional audio. They don’t say a word, but the specificity of their movements- the squinting, the lip biting, the janky dancing- are enough to perfectly invoke a certain type of man the viewers are familiar with. It’s comedy gold, and, I say, it’s Dyke Camp.For the rest of this essay, the phenomena within Dyke Camp I discuss will lean toward the masculine, but I do want to state again that that is not the only form Dyke Camp takes. Dyke Camp is just as easily present in the hyper-feminine, like can be seen in every frame of the WLW cult classic, But I’m a Cheerleader.

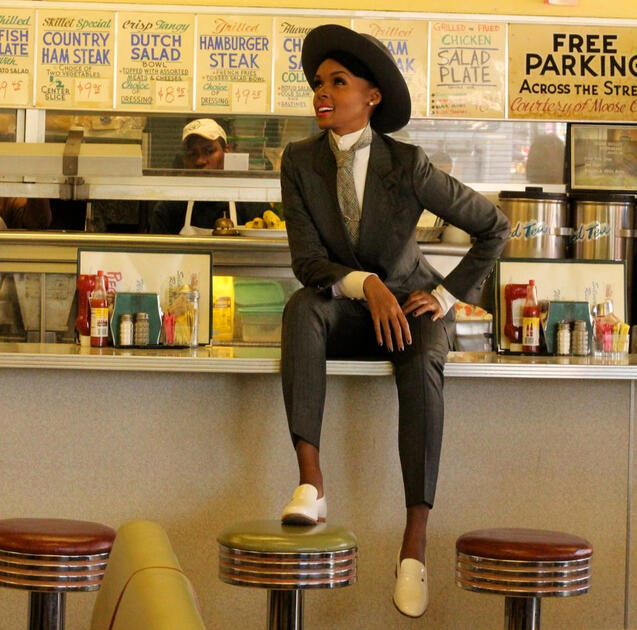

It is also, of course, very often unconcerned with such petty divides as “male” vs. “female” aesthetics. The trends I discuss are also not necessarily women channeling men. First, not everyone referenced here is a woman. Second, in Clements’ words: “Dyke camp is not reflective of or parodied from any version of maleness; it draws from … the multiplicity of lesbian identities…. Dyke camp is not simply the drag king. It’s the turned-up collar the drag king pops on his way home to his girl.”This is true. I would not call a woman straightforwardly adopting the guise of a man and doing nothing fun with it Dyke Camp. The Camp comes from the exaggeration, the comedy, the glee the performer is clearly taking from it. Janelle Monae simply wearing a suit is not Dyke Camp. Janelle Monae in full male 1950’s getup (hat and all), complete with her manspreading on the counter of a vintage diner in a pin up-style photoshoot, is.

For the rest of this essay, I’d like to add my own addition to the Dyke Camp discourse: another trope I’ve noticed quite a bit that I think should be counted in the category, but I have yet to see much discussion on. This trope is what I will call the Lesbian Lovable Loser, though I am not only open to but begging for other suggestions. For everyone’s sanity, it will be referenced as LLL from now on.The lovable loser of mainstream media- particularly film and television- is ubiquitous enough to be immediately recognizable. This is the underdog protagonist. The gangly, often bespectacled, unpopular teen star of every high school comedy of the last 50 years. This is the nerd who is hopeless with women, but somehow always gets the girl at the end of the movie. Scott Pilgrim, Steve Urkel, Leonard Hofstadter, and Sam Weir. The casts of The Inbetweeners, Revenge of the Nerds, and Superbad. Every character Anthony Michael Hall has ever played.

The LLL channels the aesthetics of this trope and makes it her own. Clements makes brief reference to an essential LLL art piece with her inclusion of the music video for queer artist Partner’s “Play the Field.” There, she highlights the duo’s “normcore sportswear, ugly sunglasses, good puns.” I’d like to add that the mere fact the trope is being evoked at all in the video’s visuals contributes greatly to the Camp. If you ask me, the “normcore sportswear” that Clements references does more than represent the everyday fashion choices of the Partner duo. Alternatively, I see it as a costume. Partner is stepping into the role of teen movie underdogs. This is made especially apparent when accompanied by the toothy posing for the camera; the 1970’s/80’s video clips interspersed throughout the video; background settings of a soccer field, basketball court, and dingy locker room; plus this title card:

It was “Play the Field” that first got me thinking about my LLL theory, in fact. I hadn’t seen the music video yet, but something clicked when I heard the bridge of the song for the first time:And I never thought that I would play a sport

But somehow there I was and the ball was in my court

Before I could figure out if it was real or just a dream

I scored my only basket of the season, it was on my own teamThe scene painted by these lyrics is as lovable loser as it comes. It is straight out of a retro high school comedy. It couldn’t exist today outside of a Disney Channel sitcom, and for that, it rings highly nostalgic. It is also a scene that would almost always feature a skinny white man. The mere fact of a woman (admittedly, a skinny white one) repeating it instead brings an element of awareness to it that otherwise would not exist. Simply delivering the line is made Camp.This is, of course, elevated x1000 by the video. Partner slip into their roles as easily as Michael Cera or Jonah Hill. With the signifiers they provide, we as an audience know exactly who they are in our cultural consciousness. Visual gags, such as the following alluring shot, add to the fun, and perhaps the Camp.

The unseriousness of the work is reinforced, and it becomes clear that this piece of art is self-aware of what it's invoking. That said, whether that awareness makes the performance feel more ironic is debatable, which is also part of the appeal.Beyond music, this trope has claimed its place across all mediums that allow for it. The “me gay” scene from One Day at a Time (2017), featuring daughter Elena and her friend both anxiously trying to determine whether the other is also queer, is infamous on the WLW internet as a relatable depiction of Sapphic “uselessness” in dating.

Sam, the questioning teenage lesbian of Blockers (2018) is adorkable in her sweaters and thick glasses. She also photoshops herself onto the arm of Xena: Warrior Princess in her spare time. Jillian Holtzmann of the all-female remake of Ghostbusters (2016) sports bright yellow goggles and a shock of frazzled mad scientist hair. This, plus her ill-fitting blue collar attire really bring the Dyke Camp to life.

Booksmart (2019) made queer, and Dyke Camp, history when it did the Superbad “nerds sneaking into a cool kid party” premise with a lesbian protagonist at its helm. Amy Antsler’s femaleness doesn’t spare her from any teen comedy-typical embarrassment, as is evidenced in this notorious scene: (NSFW + emetophobia warning)

This phenomenon can also appear when female actresses perform male characters with no attempt at hiding their underlying selves, so that the audience is made totally aware of the drag they’re performing. Lauren Lopez’s cross-dressing performance as a whimpier, goofier Draco Malfoy who is frequently struck by spells of rolling around on the stage in A Very Potter Musical certainly constitutes this.

The same can be said, I think, with Beth May’s performance as Ron Stampler, the clueless stepdad, in the Dungeons and Dragons podcast Dungeons and Daddies.

Ashly Burch, creator of the early Youtube series Hey Ash, Whatcha Playin’? is a visionary in her contributions to the LLL archive. The version of herself that appears in Burch’s sketches (usually only 2-3 minutes long) is every LLL trope made perfect. She is too dumb to live, constantly speaking in baby talk, making dirty jokes, and failing to perform basic tasks. At the same time, she has complete confidence in herself as a pro-gamer, and a smooth, girl-catching Casanova. There is no self consciousness from Burch. She is hardly aware of her status as a woman, let alone as a lesbian. Her character simply exists and does her best, while the world around her reacts with bewilderment.

TikTok (or rather, #queertok), when it is not serving as a hub for the lesbian seduction-as-performance Camp that it also loves, is home to mountains of this style of dorky, relatable comedy as well. These brands of videos have no concern with being consumed by heterosexual outsiders. They are plainly made by Sapphic women, for other Sapphic women- as evidenced by the plethora of comments reading “I am no better than a straight man” that inevitably appear on all of them.The LLL archetype can appear in a one-off video, or be the whole of a creator’s persona. It’s visible in the outfits they wear, their manner of carrying themselves, and the jokes they tell. The struggles the characters experience are those of the nerd of mainstream culture. They can't get chicks. They try to hit on women and they're terrible at it. Still, they can’t help but fancy themselves a smooth-talking ladies’ woman. They, in this case particularly because as women they know what it's like, try not to objectify other women, and fail.

There is an elephant in the room regarding this trend that I think warrants some discussion. That being the underlying political incorrectness of leaning into these tropes at all. The mainstream manifestation of the lovable loser trope has already had quite a reckoning in the past decade or so. As more and more real-life accounts come to light, it has become increasingly clear in the public consciousness that misogyny is not less harmless when it comes from a “nerdy” source, and antisocial men are not less invested in the upkeep of sexism. I remember the collective realization that self-proclaimed “nice guys” are more often actually entitled creeps. Then, the belated backlash to lovable loser classics like American Pie (1999), Sixteen Candles (1984), and, again, Revenge of the Nerds (1984), for consistently portraying sexual harassment and even assault as a mostly harmless, if somewhat pitiful, activity. It makes me wonder if invoking similar tropes is not inherently playing with fire.In his video essay, The Adorkable Misogyny of The Big Bang Theory, Jonathan McIntosh examines the sitcom The Big Bang Theory (2007). He observes that when its prototypical nerd main characters partake in chauvinism, the butt of the joke are never the misogynist words or actions themselves. Rather, the laugh is on the “unmanly” men who are unable to convincingly pull them off. When I laugh at the internet WLW equivalent of this humor, I wonder if I am not enabling something similar.

I do think it will be important for creators to remain vigilant of what ideologies they’re promoting as this trend continues. For the most part, however, I am not exceptionally concerned. Most examples I have come across utilize a softened, more palatable form of the lovable loser trope. Some cherry picking occurs, with the fun, nostalgic parts being recreated and the more distressing elements removed. Like their male nerd predecessors, the characters performed by these creators are socially awkward, geeky, horny, desperate to be liked- and yet earnest, hopeful, and trying their best.This, as it is with the sympathetic parts of the mainstream lovable loser archetype, is appealing. Additionally, when played by queer women in 2022, there is an added layer of nostalgia, irony, and even reclamation, I would argue. In the real world, the queer women voicing these sentiments would more often be, or at least be expected to be, the recipient of these types of blustering, social awkwardness-induced hijinks. Perhaps there is some catharsis in occupying these roles that are typically reserved for (straight) men. While the male lovable loser shirks the mainstream ideal of the confident, ultra-masculine man, while still winning the hearts of audiences and his love interest, maybe the LLL gets to set aside traditional femininity altogether.This “traditional femininity,” includes all that going through the world perceived as a woman entails. It is the need for a mainstream approval of her performance as, not only a feminine woman, but an object of desire. Someone who is looked at, objectified, scrutinized by the male gaze. Someone who is seen, rather than does the seeing. That is one important trait of the Lesbian Lovable Loser: she does the seeing. It seems often to not even occur to the characters these women play that they may be observed by an audience, especially not a male one. Even if it means taking on a maligned persona, I can see the relief in that.I also believe that, as a whole, this reclamation of the male, heterosexual gaze is an important element that makes Dyke Camp different from traditional Camp. Even when Dyke Camp involves performing to be admired, it is with a necessary understanding of who that performance is for. Dyke Camp is codified with, and enriched by, as Clements puts it: “ women who know just how to touch and want other women.” Madonna, Britney Spears, and Christina Aguilera kissing at the 2003 VMAs for leering straight men is not Dyke Camp. Even when it is not a performance of seduction by women for women, however, Dyke Camp still draws strength from being performed in and understood by a queer in-crowd. I think one of the reasons Dyke Camp is so hard to explain and define is because of the life experience needed to understand it. Among women who have grown up queer, I have never had to explain a Dyke Camp joke. It is the lifetime of a certain type of othering that gives one the ability to “know it when you see it.”So that makes my case for its dykery, yes, but is it Camp? I would still say so. By its nature, of course, this aesthetic is not particularly Campy in the way we often think of. It is not consciously attractive, nor flamboyant, nor does it feel like a call for positive attention. At the same time, even when played by men, but particularly by women, I think it qualifies. The lovable loser- as in, the usage of the trope- is beyond being taken seriously. It is rooted firmly in visibly dated media and its elevated social structures and cheesy overacting. Stories like these can be fun and even escapist. One thing that they always are is theatrical. The LLL turns the magnifying glass of Camp from traditionally women's media, aesthetics, and performances to an aspect of mainstream male media and culture. Just because the latter is more normalized, it makes one realize, doesn’t make it less Camp.Again, some might say that these phenomena don't need naming, that to address them at all is to ruin the fun, or to add labels where they aren’t necessary. I understand these objections, and part of me holds them myself, actually. I’ll address here why I’m, personally, a fan of talking about them, regardless. Simply put, despite the progress that has been made, it still seems to me (as a lesbian woman) that queer women are considered by many to be no fun. We are the humorless sibling to queer men, the killjoy of the LGBT community. We are the serious in contrast with the flamboyant, we prefer steady dating over casual sex, we are workers while queer men are performers. Drag queens, Queer Eye, GBF’s, Glee, and Camp itself- those worlds are reserved for queer men and straight women.That popular conception really grinds my gears. We lesbians are super fun! Of course we have a sense of humor; we have to to get by. Additionally, we are plenty familiar with the theatricality, the self-deprecation, and the tongue-in-cheek presentation that is vital to Camp. Lesbian culture- which does exist, hidden as it may be from the mainstream public, even compared to its gay male counterpart- is full of drama, and I hope this essay have evidenced that in some small part. So, I can’t speak for Clements, but the reason I personally care to examine Dyke Camp is my belief that doing so is one step in the direction of acknowledging a positive part of our culture that is still largely ignored.The element of delight is crucial to Camp. Camp isn't liking something ironically, or considering something "so bad it's good." As Christopher Isherwood explains in his novel, The World in the Evening (1954), which predates Sontag’s essay by a decade: “You thought it meant a swishy little boy with peroxided hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich? Yes, in queer circles they call that camping. … You can call [it] Low Camp. … High Camp always has an underlying seriousness. … You're not making fun of it, you're making fun out of it. You're expressing what’s basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance. Baroque art is basically camp about religion. The ballet is Camp about love. …”But Mr. Isherwood, wouldn’t you agree that all Camp is Camp about love?

by Delfina Booth

Sources

Audrey Gunn, Rhea Ashley Hoskin, Karen L. Blair. “The new lesbian aesthetic? Exploring gender style among femme, butch and androgynous sexual minority women.” Women's Studies International Forum, Volume 88, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102504.

Clements, Mikaella. “Notes on Dyke Camp.” The Outline, The Outline, 17 May 2018, https://theoutline.com/post/4556/notes-on-dyke-camp.

Isherwood, Christopher. The World in the Evening’’. University of Minnesota Press. 2012 ISBN 9780099561149 p. 10-11

McIntosh, Jonathan. “The Adorkable Misogyny of the Big Bang Theory.” YouTube, Pop Culture Detective, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3-hOigoxHs.

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Presents ‘Camp: Notes on Fashion’ for Its Spring 2019 Exhibition”. Vogue. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

Sainsbury, Cara. LGBTQ+ Content on TikTok and Everyday Activism. 2021. Utrecht University, final master’s thesis.

Sontag, Susan (Fall 1964). "Notes on 'Camp'". Partisan Review. 31 (4): 515–530.